Published on October 11, 2019

My rewrite of the WSJ article: “The Seven-Year Auto Loan: America’s Middle Class Can’t Afford its Cars.“

Financial innovation is adding fuel to an industry that keeps raising the bar for what to expect from the driving experience. Walk into an auto dealership these days and you might walk out with a seven-year car loan.

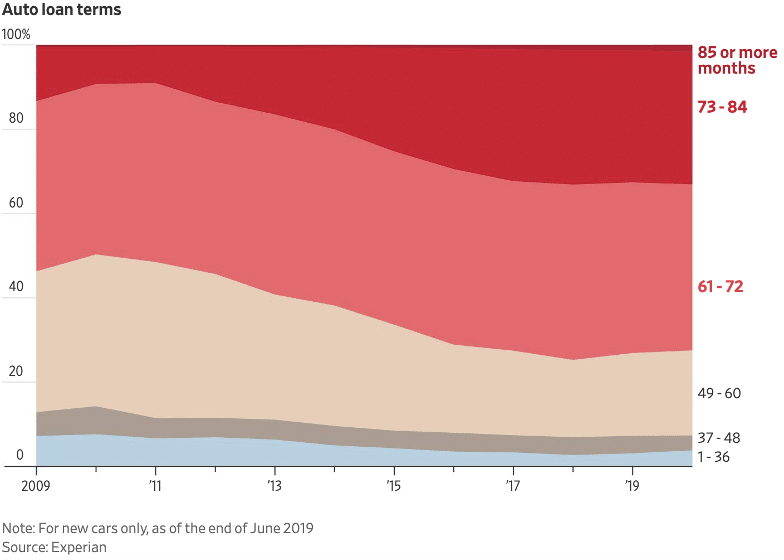

Unlike the time it takes to digest chewing gum, seven years isn’t a myth. An increasing number of car buyers are electing to extend their payments. About a third of auto loans for new vehicles taken in the first half of 2019 had terms of longer than six years, according to credit-reporting firm Experian PLC. A decade ago, that number was less than 10%.

The Wall Street Journal recently published an article titled: “The Seven-Year Auto Loan: America’s Middle Class Can’t Afford Its Cars.” I tweeted that the same set of facts could have supported a more positive story. Here is my suggested rewrite. In many places, I preserve the authors’ original language. Read and compare.

This is enabling more Americans than ever before to drive cutting edge technology. But not everyone views this as a positive development. Some suggest this is a pronounced sign that American middle class buyers can’t afford a middle-class lifestyle.

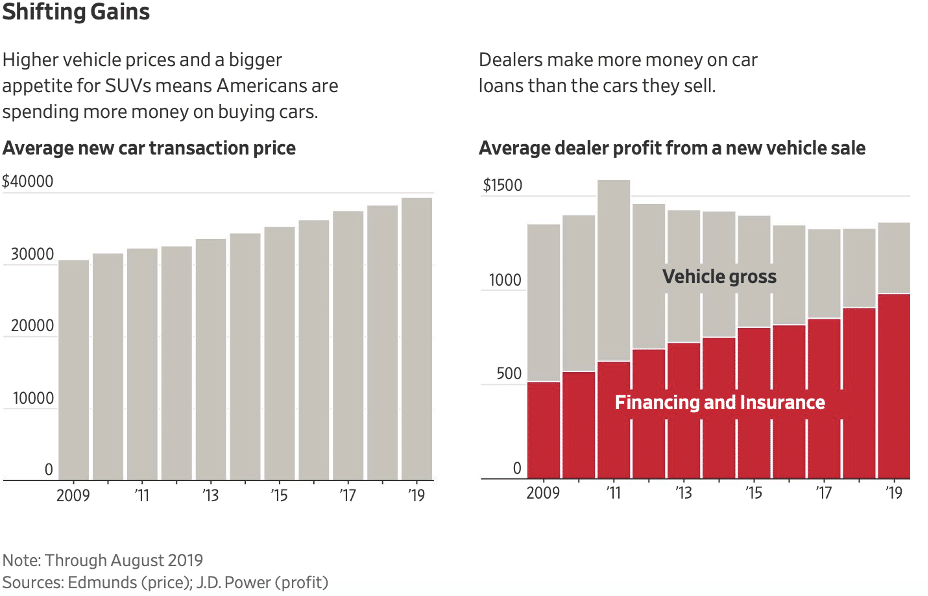

This view is based on the perception that incomes have risen at a sluggish pace in the past decade, while car prices have grown rapidly. Costly new technological and safety features, such as lane assist and larger and more sophisticated multimedia displays, are making their way to even the most basic cars. U.S. consumers have also veered toward pricier rides such as sport-utility vehicles that tend to dominate auto showrooms.

The result? Consumers are seeking bigger loans than ever to purchase a car. And the only way they can afford them is to stretch out the payments.

Growing Dues

But this perception masks a brighter reality. The truth is that cars have never been more affordable, and even the most basic models include features that have forever changed our driving experience. Trying to imagine life before backup cameras is like trying to imagine life in a city before rideshare. You can’t.

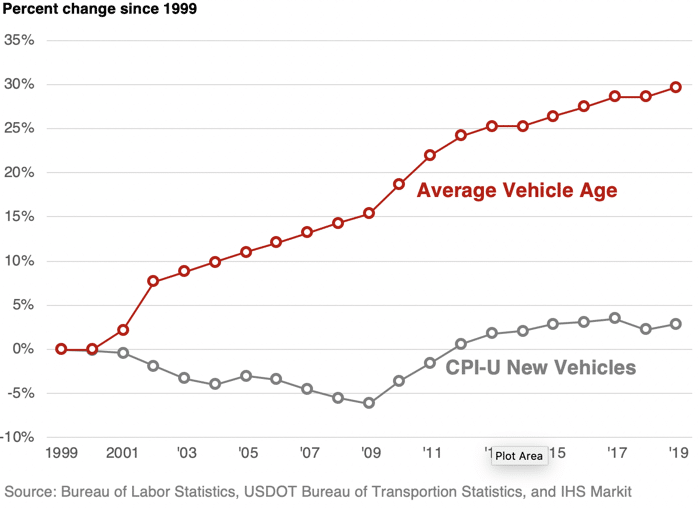

The consumer price index for new vehicles has risen only 2.9% over the past 20 years. When compared to 54% inflation over the same period, prices have dropped in real dollar terms – same model cars cost about a third less than they did in 1999. And cheaper cars don’t mean cheaper quality. Vehicle life expectancy has steadily increased. The U.S. Department of Transportation’s Bureau of Transportation Statistics now puts it at 11.8 years, a 30% rise since 1999. This is well beyond the longest term of loans on offer. “Better technology and overall vehicle quality improvements continue to be key drivers of the rising average vehicle age over time,” says a recent IHS market report.

Longer Life for Less

Higher quality cars without a commensurate increase in cost

Cars that last longer, take less of our paycheck, and come with enhanced features is a welcome consumer development. Wall Street has been adjusting its practices to accommodate this new paradigm. Improved quality and longevity make it possible to spread the debt over longer periods.

The average loan now stretches for roughly 69 months, a record. Some last much longer. In the first half of the year, 1.5% of auto loans for new vehicles had terms of 85 months or longer, according to Experian. Five years ago, these loans were practically nonexistent.

Stretched-out Debt

Auto loans are increasingly getting stretched out to keep payments manageable.

There is a potential downside to this new trend. For many Americans, the availability of loans with longer terms can create an illusion of affordability. It enables car purchases that would have previously been out of reach with three-, four- or five-year loans.

One 22 year-old customer walked into a Honda dealership in early 2017 after a salesman emailed him and said he might be able to buy a new car for less than $400 a month.

He walked out with a gray Accord sedan with heated leather seats. He also took home a 72-month car loan that cost him and his then-girlfriend more than $500 a month. When they split last year and the monthly payment fell solely to him, it suddenly took up more than a quarter of his take-home pay.

He paid $27,000 for the car, less than the sticker price, but took out a $36,000 loan with an interest rate of 1.9% to cover the purchase price and unpaid debt on two vehicles he bought as a teenager. It was particularly burdensome when combined with his other debt, including credit cards, he said.

Stories of young consumers taking on too much debt are all too common. Looking at payments alone has always been a consumer trap, and longer available terms put inexperienced consumers at even greater risk. The silver lining for this 22-year old is that he was able to bundle his old debt into the new car low interest rate. Many consumers aren’t so fortunate. Carrying debt from an old vehicle to a new one may be one reason why the size of the average auto loan has grown by about a third over the past decade to $32,119 for a new car, a figure reported by Experian.

Upside Down

A growing share of buyers won’t pay off their debt before trading their car in for a new one.

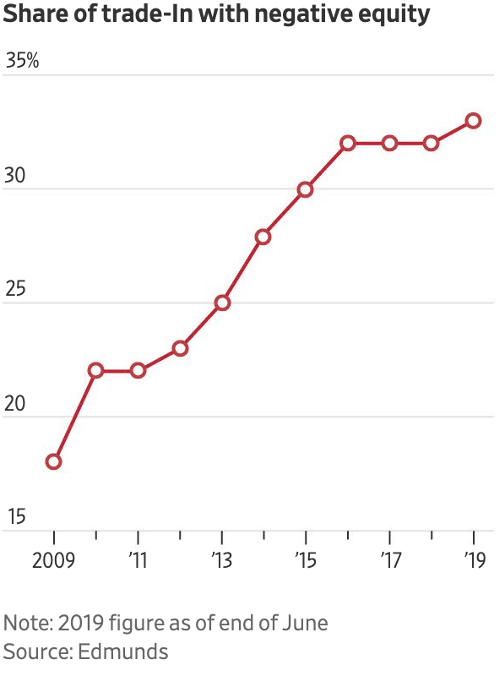

A third of new-car buyers who trade in their cars roll debt from old vehicles into their new loans, according to car-shopping site Edmunds. That is up from about a quarter before the financial crisis.

For some consumers, this could be a sign of fiscal imprudence. New cars depreciate most rapidly in their first few years, and trading in too soon can lead to negative equity – when the car is worth less than owed. As loan terms continue to increase with vehicle life expectancy, consumers may need to recalibrate their car-changing decisions.

For other consumers, the allure of continuing low interest rates and technological innovation may be driving heightened consumption. Each year pays witness to a new feature that tempts even the most recent buyers back to the showroom. Trading up while the rates remain low can be a rational choice for financially secure buyers who want to ensure having the latest safety or comfort enhancements.

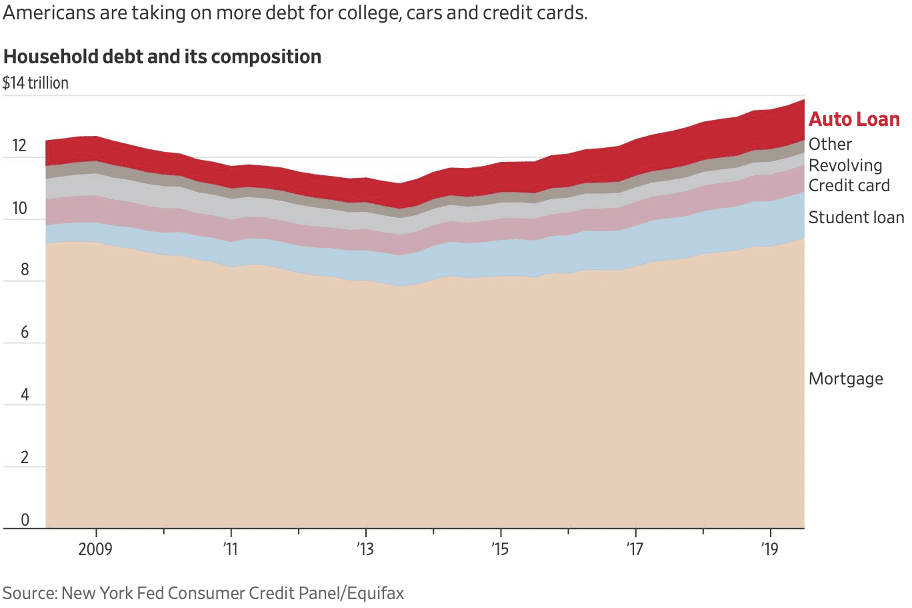

The result of low-for-long rates is auto debt that has swelled since the financial crisis. U.S. consumers held a record $1.3 trillion of debt tied to their cars at the end of June, according to the Federal Reserve, up from about $740 billion a decade earlier.

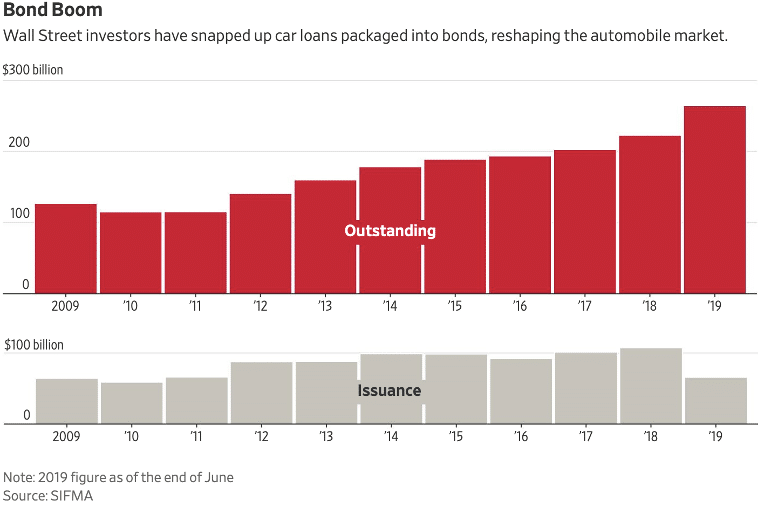

Wall Street investors have snapped up car loans packaged into bonds, reshaping the automobile market.

The growth has been a boon to an auto industry that a decade ago flirted with disaster. The onset of the financial crisis left many consumers without the cash to go car shopping. When the Federal Reserve lowered rates to practically zero, it became much cheaper to finance a car. And loans made to buyers were packaged into bonds that institutional investors found attractive compared to the returns from low yielding Treasuries.

The combination of low rates and an efficiently functioning U.S. capital market helped bring the U.S. auto industry back to life.

Fast forward to last year, investors bought a record $107 billion of bonds backed by cars, according to the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association, a trade group. That is a level of economic strength not seen since before the crisis, when it reached the previous record $106 billion in 2005. Institutional investors now have a record $264 billion in auto bonds packaged in their portfolios.

The efficiency of capital markets has also helped dealers stay afloat. As profits from new car purchases continued to get squeezed by online and other consumer buying programs, they have found a lifeline in lending.

So far this year, dealerships made an average of $982 per new vehicle on finance and insurance versus $381 on the actual sale, according to J.D. Power, a data and analytics company. A decade earlier, financing brought in $516 per car and the sale made dealers $837.

While dealers aren’t profiting from consumer sales any more than they did a decade ago, these shifts signal where car buyers need to focus negotiating skills – in the dealership’s finance office.

Dealers affectionately call it “the box,” a reference to the holding cell to which Paul Newman’s character was sent in the 1967 movie “Cool Hand Luke.” Since most buyers borrow to pay for their cars, they do better when they walk into the box informed about their options, including a manageable payment schedule.

The dealership commonly holds on to a portion of the interest rate, typically between 1 and 2 percentage points, or gets a one-time payment from the lender. The dealer also pitches high-margin add-on services, such as extended warranties and insurance for dings and dents, which are rolled into the loan.

When some buyers enter the box, they might not fully understand the cost of these add-ons because of how they are presented. Unscrupulous finance managers might quote a price in which the add-ons are already bundled into the loan amount to increase the bottom line, a tactic known as “packing the payment.”

Many consumers find themselves unprepared for the hard sell from the finance manager. Even when they know how much they should pay for the car, they might still have a hard time saying ‘no’ to add-ons they don’t need.

The efficiency with which the loans are processed is impressive. Finance managers at dealerships typically use an electronic portal to hash out the terms of the loans. On the other end are various financial institutions that buy up the loan pretty much as soon as the dealer closes the deal.

Banks and credit unions are big lenders, as are the finance arms of major car makers. Some of these lenders shunned riskier subprime borrowers after the financial crisis, fueling innovation and the growth of independent nonbank auto lenders.

The billionaire owner of one of the biggest subprime lenders got his start lending four decades ago when, as a dealer, he realized subprime buyers needed somewhere to get their financing. His company is still focused on these borrowers, but it has pursued more creditworthy customers as it has grown in recent years.

Much like a dealership, the company is obsessed with results. An automated system sends emails to employees with an image of a winking robot when they are late to work, unproductive or exceed expectations. Workers get monthly bonuses based on how they stack up against their goals. Screens around the office display auto loan applications as they come in.

The company needs to make sure the monthly payments on its auto loans keep flowing. Late borrowers can expect calls from the company immediately. Roughly 40% of its employees focus exclusively on collecting.

In mid-April, a representative who handles the most-difficult cases called a past-due borrower to iron out a payment on a 2018 Toyota RAV4. The borrower had struggled to keep up with a payment of more than $800. The car already had been repossessed from the borrower once.

The representative switched between English and Spanish. He offered an extension on the March payment, meaning it wouldn’t be due until the end of the loan in 2024. But he collected nearly $600 on a partial payment for April over the phone. Borrowers are less likely to resume payments if they stop altogether. After hanging up, the representative rang a bell at his desk. “35K,” he called out, referring to the balance of the loan that was no longer considered seriously delinquent. “It took a while but I got ’em.”

Debt in America

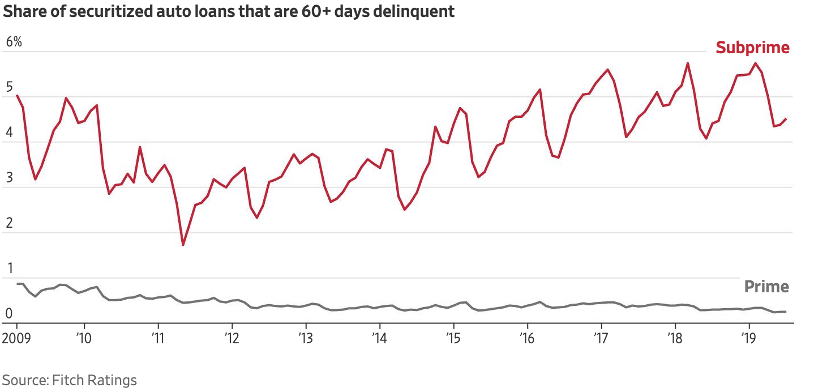

Across the industry, delinquencies have trended higher in the past few years, but they haven’t surged like mortgage delinquencies did during the financial crisis. Investors have been largely content to buy lenders’ auto bonds as they search for returns in a low-rate world. Losses are significantly higher when loan terms lengthen, according to S&P Global Ratings.

Many borrowers secure their financing from the lending arms of car manufactures, like Honda’s financing arm, which pools a large portion of its loans into bonds that it sells to investors. A $1.25 billion sale from late 2017 contained more than 7,000 loans tied to 2017 Accords like the one our 22 year-old borrower owns, according to loan-level data.

The investors who hold his loan are still getting paid because he has remained current. Committed to fulfilling his obligation, he took on more overtime shifts at the plastic factory where he works as a machine operator. A raise and a bonus helped get him to stable ground. Still, it may be a while before he is comfortable with his financial situation. He says he doesn’t plan to take out another auto loan soon. “Even just signing the paper, not even driving the car off the lot, suddenly I’m underwater,” he now recognizes as a long-held truth for new car buyers everywhere.

Postscript

This LinkedIn post reflects the edits I would have suggested to Ben Eisen and Adrienne Roberts in their WSJ Article: “The Seven-Year Auto Loan: America’s Middle Class Can’t Afford Its Cars”.

Upon reading their original version I was struck by how they interpreted the data. It didn’t align with my experience as a financial economist and former market regulator. I responded by tweeting that I could use these same facts to support a positive story about continuous improvements in auto technology and efficient capital markets.

That night I began thinking about ways to turn this into an exercise for a finance class I plan teach next semester – ask students to rewrite the article to support an alternative hypothesis using the same underling data. A critical thinking exercise.

The next morning, by happenstance, I had breakfast with a prominent Columbia University economist. We discussed his recent paper on Media Power, which proposes a new way to measure media influence based on attention rather than market share. He wrote it to help governments better understand media’s role in shaping democratic decision-making for the purposes of antitrust regulation.

I decided then that the issue was important enough that I would follow through with the proposed exercise myself.

My goal is to remind readers that ‘fake news’ is not the only concern when considering your sources. How verifiable facts are presented is just as important as ensuring the facts are verifiable. Journalists can shape reader perceptions without ever telling a lie, and this can be a problem when there is a better truth to be told. I believe that to be the case here. Or so this exercise is intended to demonstrate.

In my view, the original article provides an unbalanced discussion of the data. The result is a misrepresentation of the U.S. economy and welfare of the American middle class.

The overarching truth is that much of the American middle class would not have access to cutting edge automotive technology if not for the financial innovation that allows them to pay for it as they consume it. As assets become longer lived, it is natural for them to be financed over longer periods. That is not nefarious in intent or practice.

To be sure, and as illustrated by the article, excesses taken by car shoppers caught in the moment can result in significant financial stress. And predatory behaviors in the auto industry have long existed, and will continue to exist, regardless of the terms of loans offered. We all have a story to tell about our time in the ‘box’ and the ‘learning’ that ensued from our mistakes. And some of the stories are terrible. But the seven-year auto loan is not responsible.

Auto bonds – or, more formally, bonds securitized by auto loans – were not the cause of the last financial crisis and they are unlikely to be the cause of the next. The auto loan market is fundamentally different than mortgage loan market and does not have the same destructive ability. Even so, regulation of auto loan securitizations was strengthened in 2014. Under the leadership of then SEC Chair Mary Jo White, rules were adopted to increase the transparency of loan level disclosures and bring greater investor awareness of potential risks in the market.

The current growth in auto lending and resulting securitizations is a welcome manifestation of the low-for-long interest rate environment promoted by the Federal Reserve bank to spur economic recovery. Consumers are doing exactly what was intended – they are driving wealth and prosperity to all segments of the economy. A loan is a promise of the future, and households and companies are making the types of promises that helped lift the economy after the crisis.

The current rise in delinquencies could very well impact the returns of auto bond investors. Subprime lenders could also take a bath. And if this happens, pundits will point with good reason to the current rise in debt as evidence that excesses were taken. But it won’t be evidence that markets weren’t working as intended – risk and failure are necessary ingredients to efficient capital markets. Subprime lending is playing its part – providing access to capital for borrowers who might otherwise have none.

With these ideas in mind, I set out to rewrite the original article. I started by transferring the article into a MS word file and turning on ‘tracked changes’ to assess the edits I thought it deserved. I quickly realized that I needed some rules of engagement. Here is what I came up with.

- I would preserve as much of the storyline as possible. I didn’t want to create a new story. I wanted to provide an alternative view of the existing story.

- I would use all their same data. I didn’t want to be accused of ignoring inconvenient truths. But I would add my own data where necessary to support my interpretation. This resulted in one new chart.

- I would aim to keep the same word count. Adding length allows more points, nuance, and caveats, but I wanted to hold myself to the same journalistic space constraints they faced. It turns out that I needed more words.

- I removed the pictures and names of those interviewed. I thought they added great color, but I did not believe it appropriate to bring them into my exercise without their permission. I otherwise kept the anonymized details. The cover picture is of one of my sons, showing off his driving skills.

- The original article extends some of the authors’ previous work. In several places they linked to that work. I preserved the links, even when I edited the overlaying sentences. So, not all of the links are perfectly on point.

As an academic I’m very sensitive to copyright and attribution. But I’m not a lawyer and did not consult one on whether this exercise would infringe on the rights of the authors or WSJ. I hope my exercise is viewed in the spirt it was undertaken – to demonstrate the dependence of conclusions and interpretations on how facts and descriptive data are presented.

Importantly, and to reiterate, I am not criticizing the veracity of the authors’ data. I fact checked where I could and did not find any reporting errors. In some instances, I could not find the source data, or it was analyzed by the WSJ without enough explanation to replicate. But nothing struck me as inconsistent with my priors, and I have researched and taught about many of the issues and regulation underlying the securitization of loans for more than a decade. In the end, I hope my version of their article shows – if you compare the two – that the underlying issues are more nuanced than originally presented, and that it is easy to conflate the benefits of financial innovation with the excesses that consumers sometimes take. Finance is a tool not the villain.